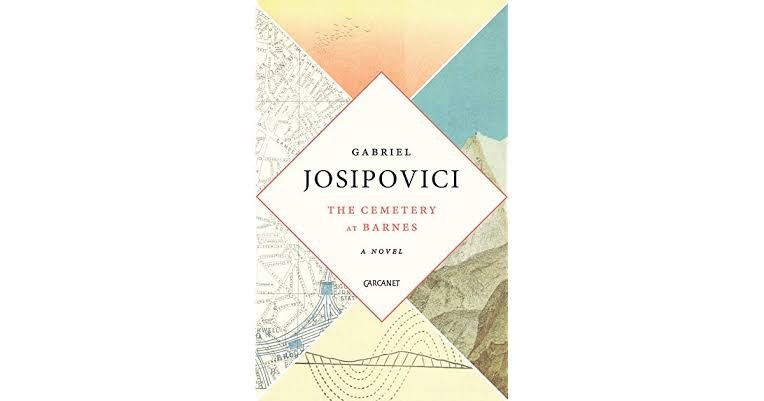

I remember once mentioning to one of my friends that Josipovici create stories that leaves much to the imagination of the reader (which he agreed to my relief), who kinda partakes on the creation. Though I fail to explain exactly what I mean by the vague term “leaving to the imagination of the reader”.

But if you are interested in what it exactly means, you just need to read this short book which attains such beautiful rhythmic, musical (3 movement) structure that has (as all great musical pieces) both minor and major keys placed in gliding succession, which seamlessly merges three separate brief episodes (1 – the protagonist is living with his first wife in london (who will die), 2 – alone in Paris, post – first wife’s death, diverting him with his translation works, 3- with his second wife in Wales, Abergavenny) with moods alternating between serene, calm, warm, tender, passionate feelings and brooding, terror, shock and apathy.

Also, with all these, you can savour lot of literary quotation and discussion on both French and English poetry, since the protagonist is a translator.

This is how it starts:

He had been living in Paris for many years. Longer, he used to say, than he cared to remember.

When my first wife died, he would explain, there no longer seemed to be any reason to stay in England. So he moved to Paris and earned his living by translating.

In Paris, he steadfastly follows an internal timetable with which he carries out his – work, eating and walking.

While getting into his apartment at Paris, he has a particular way of getting to it:

He lived in a small apartment at the top of a peeling building in the rue Lucrèce, behind the Panthéon. To get to it you went through the dark, narrow rue Saint-Julien and climbed the steep flight of steps which brought you out directly opposite the building. There were, of course, other ways of getting there, but this was the one he regularly used. It was how, in his mind, his little flat was linked to the outside world.

And that steps, her second wife notes (note the fact that this story has three interlinking episodes in the life of protagonist) :

You thought of alternative lives as you climbed the steps up from the rue Saint Julien, she would say. You thought of them as you descended.

The contrast between his first wife (violinist by passion, red hair piled up high on her head) to his second wife is striking, ( one who has no taste in classical music, mass of red hair piled up high on her head) and most of their (with second wife) conversation has a particular rhythmical charm , which gets enhanced by their repetition throughout the book.

A sample of that:

Time stands still when you are working, he would say.

Time never stands still, his wife – his second wife – would say.

For me, at the time, it did.

But it never does.

As you will.

No, she would say. Not as I will. It never does. Period.

You are right, of course, he would concede, but, since I felt it did there was a sense in which it did.

He can’t get rid of me that easily, she would say, laughing her full-throated laugh. He thinks he can but he can’t.

It’s not a question of getting rid, he would say, it’s a question of perception.

And you perceived time standing still?

Sometimes.

Sometimes, sometimes, she would mock him.

It was like a repetition of their marriage vows, and the guests were sometimes tempted to clap at a particularly pithy exchange.

I thought when my first wife died my life had come to an end, he would say.

Nothing comes to an end. You never leave anything behind. It always catches up with you.

Perhaps.

No perhaps. It never comes to an end. Not till the end comes.

Apart from these, there are two to three encounters with different (?) women.

While on one of his walks he suddenly encounters a female (with description that reminds us of both his first and second wife – red hair piled up) and in a flash they end up in her room and he returns to his room like a drunkard and crashes off to his bed.

Then in London, in an empty cafe, he tries to strike up a conversation with a lady and though hesitant she is, they end up deciding to meet at a place at a said time. But on the day he watches her from a safe distance and once she starts to leave — after waiting for him — he trails her till her home.

Both these short episodes come and go quickly, but leaves us wondering about them and their role in his life. And both these women have some traits in common with his wives.

He is a translator of French books into English, and he views all the stories he works as cardboard boxes, resolutely repeating in dimension, and pours over his favorites Du Bellay and Shakespeare.

Few quotes from Shakespeare repeats throughout:

Affection is a coal that must be cooled

Else, suffered, it will set the heart on fire.

The sea hath bounds, but deep desire hath none;

Therefore no marvel though thy hope be gone.

As we all know, favoured poem is a reflection of the reader’s mind.

Before ending this review, let me leave with the ending lines of the book (which comes in the earlier parts too – but attains a different flavour):

I sank I would feel quite relieved, he would say. I would think: There goes another life – and know I had not finished with this one.

One sprouts so many lives, he would say, and look at her and smile. One is a murderer. One an incendiary. One a suicide. One lives in London. One in Paris. One in New York.

One, one, one, she would echo, mocking him (the second wife).

With his grey hat pulled low over his eyes he climbs the stairs out of the rue Saint Julien.

Note the word echo and that he descends the steps in Paris.

Highly recommended.